The past few weeks have been exciting for the Team VA—our group of five students in a Harvard Kennedy School field class about tech and innovation.

After the initial problem definition and immersion phase of the project, we began prepping for research. We explored a variety of design research methods under the tutelage of Dana Chisnell and crafted a plan, including a recruiting screener and interview guide.

We then reached out the Boston veterans’ community, as well as our own Harvard and MIT networks to identify participants for research. We were pleasantly surprised by the number of responses from our initial canvassing email, and spent a few days calling folks for a second screen, to ensure we got a good mix of branch of service, age, gender, and life stage. We decided to target a combination of in-depth interviews (30-45 minute conversations, ideally in person) and intercepts (~10-15 minute conversations) to get the broadest swath of perspectives.

Meeting Veterans Where They Are

Our first foray into user-centered design with veterans was a morning trip to the Boston VA Hospital and the JFK Building, to meet as many vets as we could in an environment where they were comfortable. There, members of the team encountered a variety of servicemen, and spent a few hours getting to know them, and hearing their stories. Concurrently, we began holding more in-depth interviews with Boston-area veterans in person, and over Google Hangouts.

Meet Joe B.

We spoke to Joe*, who served in the Army for over ten years, starting as a private and spending the majority of his time in Special Operations from the Rangers to “Delta Force”. Upon his return to civilian life, Joe’s initial claim for disability benefits was rejected because he missed a mandatory appointment due to an overseas assignment. He appealed this claim, and four months later, received an initial disability rating, which he still felt did not reflect his true disability, which he is again in the process of appealing.

Talking with Joe, we began to truly understand the complexity of the process for the veteran appealing a claim, from simple things like misinformation of address, to bigger things like not knowing who to ask for help. Joe stressed that his frustration was not unique, that he had plenty of buddies going through similar barriers to care, and mentioned he knew at least “5 friends who didn’t even file” due to this difficulty.

Kicking it with Kara

We also spoke with Kara*, who served with the Air Force for most of her twenties, and is now living with her husband in Boston, and applying to grad school. Kara was one of the first of her female classmates from the Academy to separate from the service, and was shocked by the lack of information she received during her Transition Assistance Program (TAP) on filing a claim. At the time, she was based overseas, and was cognizant that the amount of time spent detailing disability claims may have varied by region, but she ended up doing the majority of legwork herself, once she had separated. Due to the nature of her service, she suffered both physical and mental afflictions, and felt it was important to get treatment. She credits her extreme organization to her ability to file a claim and receive a disability rating that she felt accurately reflected her injuries.

Kara now works to provide her friends with as much information as possible upon their separation from the military so that they too can access the benefits they deserve. Kara has put together a checklist and spreadsheets that she shares with friends, and had a host of great ideas for how the VA could streamline the process—including better transparency of information and better access to doctors. Kara’s enthusiasm to help our team underscored how much veterans care about each other, and how dedicated they are to improving the veterans’ experience.

Digging into the Data

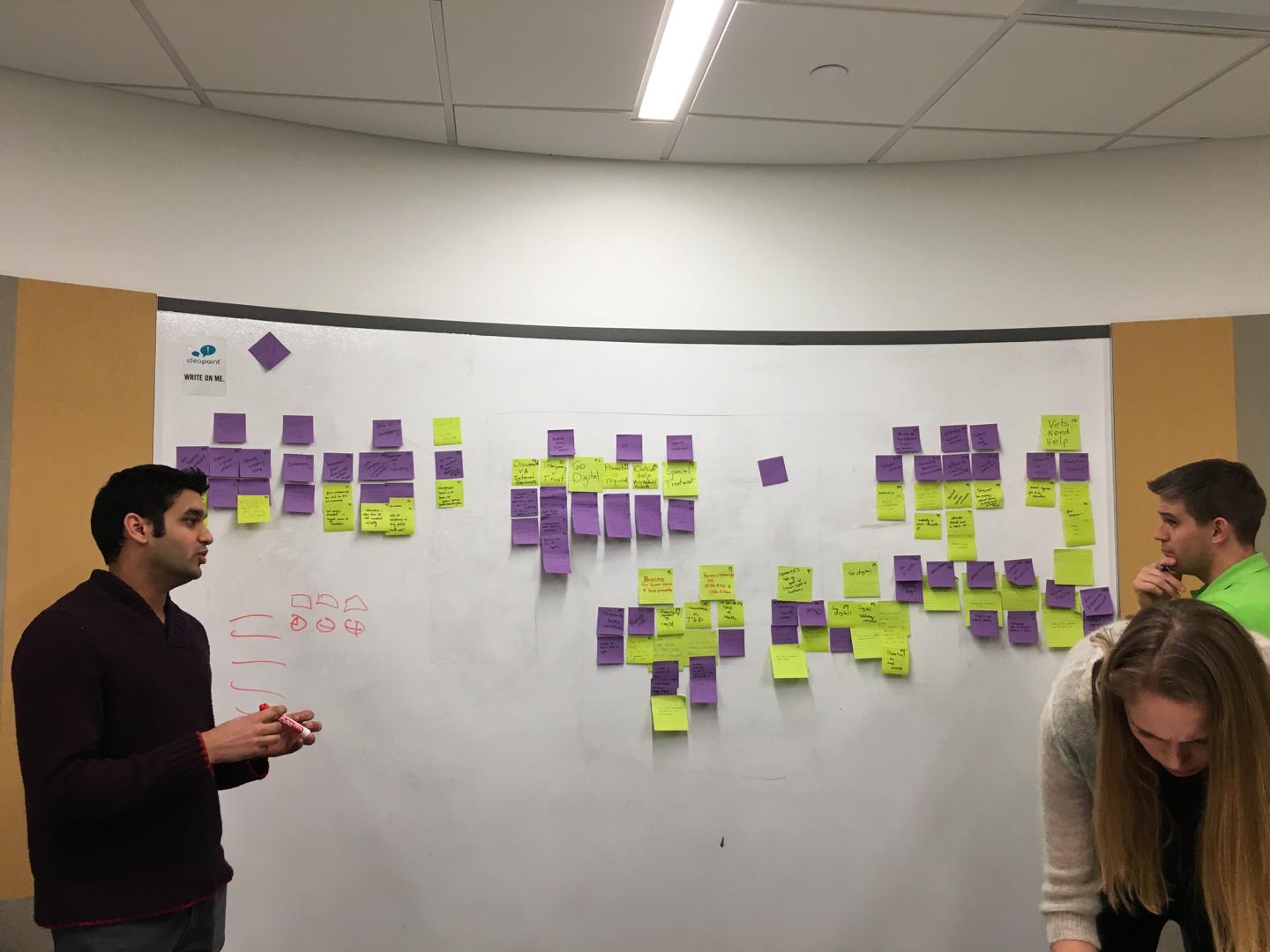

So far, we’ve spoken to almost twenty veterans about their experiences with disability claims, and the list keeps growing. Our team feels so lucky to have the opportunity to be privy to the narratives of these noble men and women, and as we move into the synthesis phase of the project, we’re looking forward to beginning to design potential solutions. As our portable “war room” fills with post-its, themes and opportunity areas are starting to bubble up… next stop, user insights!!

If you’re interested in learning more about design research, check out this list of great reads to get started.

Chetan Jhaveri, Jane Labanowski, Paris Martin, Rohan Pavuluri, Joshua Welle

*Names have been changed